Before literature became a silent, solitary act, it was a spoken one. Stories were carried by breath, rhythm, and tone long before they were confined to pages. Today, reading is largely private and internal, yet the act of reading aloud—once central to literary culture—reveals dimensions of language that the eye alone cannot fully grasp.

Voice restores the body to the text.

Sound as Meaning

When words are spoken, their music emerges. Cadence, pause, stress, and intonation shape interpretation. A sentence that appears neutral on the page may sound ironic, tender, or ominous when voiced. Poetry, in particular, is designed for the ear as much as the eye; its rhythms and patterns come alive only in sound.

Language becomes physical.

Emotion Through Breath and Pace

Reading aloud makes emotion audible. A trembling pause can convey uncertainty; a quickened tempo can suggest urgency; a softened tone can communicate intimacy. The reader does not merely understand the feeling—they perform it. This embodiment deepens emotional connection to the text.

The voice carries what punctuation only suggests.

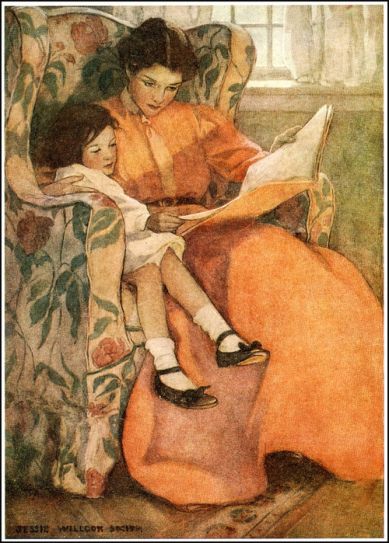

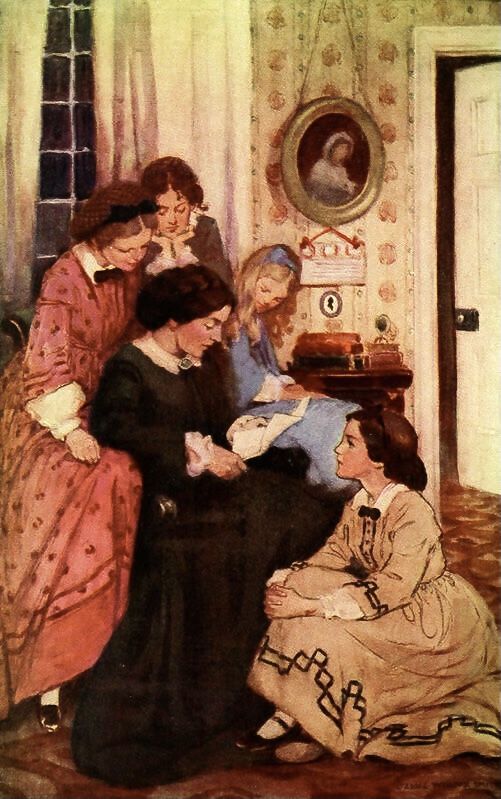

Communal Listening and Shared Imagination

To read aloud is to invite others into a single imaginative space. The story unfolds in collective time, creating a shared emotional rhythm. This communal experience recalls the origins of storytelling, where narrative was a social event rather than a private encounter.

Listening binds imagination together.

Clarity and Comprehension

Complex sentences often reveal their logic only when heard. Reading aloud exposes awkward phrasing, hidden emphasis, and structural balance. For writers, this practice is a form of revision; for readers, it is a mode of deeper comprehension.

Sound tests sense.

The Intimacy of Voice

A voice carries personality, vulnerability, and presence. When literature is spoken, it gains a human texture that silent reading cannot replicate. The text feels less distant, less abstract, more immediate.

Words become encounters rather than objects.

Why Reading Aloud Has Faded

Modern reading habits prioritise speed and privacy. Yet in losing the spoken dimension, something subtle is also lost: the full sensory experience of language. Audiobooks and public readings attempt to restore this, reminding us that literature is not only seen, but heard.

The ear reclaims its role.

Conclusion

Reading aloud reconnects literature with its oldest form: voiced, shared, embodied. It reveals rhythm, emotion, and meaning through sound, allowing language to move not only through the mind, but through breath and presence.

In speaking the text, we allow it to speak back.