In recent years, debates around book bans, withdrawn texts, and “offensive” literature have re-entered public discourse in India. From school syllabus revisions to calls for removing novels from bookstores, literature is increasingly being evaluated not for its artistic or intellectual value, but for its perceived political and moral acceptability. This renewed attention to censorship raises an important question: who gets to decide what readers are allowed to encounter?

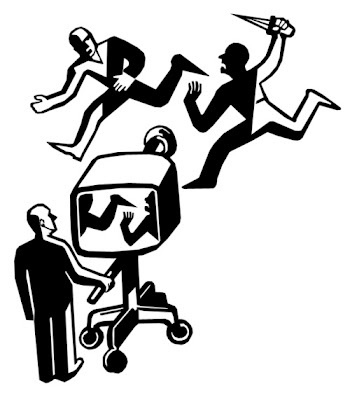

Literature has historically been a space for dissent, discomfort, and disagreement. As the often-quoted idea goes, “literature comforts the disturbed and disturbs the comfortable.” When texts are restricted or erased, it is not only writers who are affected, but readers as well. The act of censorship reshapes the literary landscape by narrowing the range of ideas available for public engagement.

Censorship Beyond Legal Bans

Censorship does not always appear in the form of official prohibitions. In many cases, it operates through quieter mechanisms: publishers avoiding “risky” manuscripts, institutions revising syllabi, or authors self-censoring to avoid backlash. These indirect forms of censorship are less visible, yet equally powerful.

In such cases, silence becomes enforced rather than chosen.

Literature as a Site of Discomfort

Many contested texts challenge dominant narratives around history, religion, gender, caste, and nationalism. Discomfort is often framed as harm, and complexity as threat. However, literature’s role has never been limited to reassurance. It exists to provoke, to question, and to complicate comfortable assumptions.

To remove such texts is to limit the scope of collective imagination and inquiry.

Readers and Intellectual Autonomy

Censorship also assumes a passive reader—one who must be protected from ideas rather than trusted to engage critically with them. This undermines intellectual autonomy. Reading is not an act of unquestioning acceptance, but of interpretation, resistance, and dialogue. Readers bring context, judgment, and disagreement to every text they encounter.

Restricting access weakens critical reading culture rather than strengthening it.

The Classroom as a Battleground

Educational spaces have become central to contemporary censorship debates. Decisions about what is “appropriate” for students often reflect larger ideological concerns. Literature taught in classrooms plays a crucial role in shaping how young readers understand history, identity, and power. When texts are removed, complex realities are often replaced with simplified narratives.

As a result, education risks becoming narrower and less reflective of lived experiences.

Why These Debates Matter Now

At a time when information circulates rapidly and public discourse is increasingly polarised, literature offers slowness, nuance, and reflection. Censoring books in such a climate does not safeguard society; it limits its capacity to think critically and empathetically.

A culture that restricts reading ultimately restricts dialogue.

Conclusion

Censorship in literature is never just about books. It is about authority, control, and the boundaries of acceptable thought. By questioning who decides what can be read, we also question who gets to shape cultural memory and imagination.

Literature thrives not in silence, but in debate.